|

In the build-up to Hollywood awards season, I noticed a theme emerging across a number of movies released in 2015. Many of the films featured claustrophobic interior spaces, violence and surveillance within the home, and women for whom domestic locations are dangerous. Here, I reflect on how women both inhabit, and are contained by, household spaces in Carol, Ex Machina and Room (all 2015). Initially, I considered including The Hateful Eight in this post, which also focuses on a single, inside space. However, owing to the film’s ensemble cast and broader narrative about the wilderness (which might be more suited to comparison with The Revenant) I have left it out of my discussion. What follows is a ‘first thoughts’ analysis of three films that all have women protagonists, domestic locations and surveillance in common. Having seen each picture once (in cinemas), my goal is to offer a brief exploration of key themes with a view to writing a more detailed piece in future.

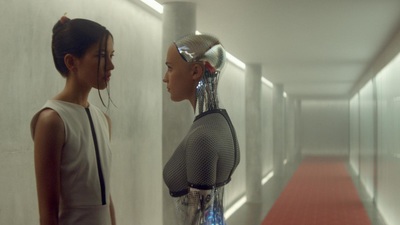

Carol, Ex Machina and Room all tell stories about women’s lives in domestic spaces that are, whether through choice or circumstance, sealed off from the outside world. Carol and Therese (Carol), Ava and Kyoko (Ex Machina), and Ma (Room) exist behind closed doors and in enclosed sites such as bedrooms, living rooms and kitchens that are typically associated with the private sphere. Yet, in each case, the privacy and safety that the home traditionally represents for women is undermined, as women’s personal lives are subject to men’s aggressive behaviours. For example, Ma, alongside her son Jack, is a prisoner in the eponymous Room. Trapped, raped and assaulted by Old Nick, Ma is confined to a world in which an antiquated TV set and a skylight offer her only connection with life outside her living quarters. By keeping Ma inside Room, Old Nick imposes physical limitations on her (also determining her diet and energy consumption), and so configures the home as a site of patriarchal control. Thus she is forced to look inward and creates narratives about the sea, the sky and the planets via domestic objects such as the bathtub. The scale of inside and outside environments are inverted, with the physically enormous becoming small, and the mundane taking on huge significance: Old Nick has the power to figuratively turn her world upside down. Meanwhile, in Ex Machina, technology entrepreneur Nathan’s spacious abode is constructed through a series of passageways, doors and glass screens that lead to dead ends in a maze-like interior. Inside the house, Ava and Kyoko are not only alienated from society by the property’s uncharted and remote location, but also from one another by circuitous designs that prevent autonomous mobility. The man-made prototype for Ava’s brain, which offers infinite possibilities for electronic pulses to find pathways within a sealed, gel structure, is a microcosm for Nathan’s home. He restrains the women residents by creating an illusory freedom of movement in an entirely restricted space; he is a spider wrapping web figuratively around, and literally through the coding of, his victims. Finally, in Carol, the protagonist and her partner Therese abandon the shops and restaurants that force them into public view in New York, and instead seek invisibility, and anonymity, in a series of rural motel and hotel rooms. For a short time their plan affords them privacy in bedrooms that are theirs to inhabit alone. However, the couple’s intimacy is subverted by both the camera’s presence at intimate moments in their relationship, and by the wires and tapes that the private detective uses to record their exchanges for evidence in Carol’s custody case. Through technology, Carol’s husband enforces his presence in the couple’s makeshift homes. In doing so, Harge, the uninvited guest, penetrates and so destroys the shelter the women seek within domestic space. In Carol, the rooms infiltrated by the hired ‘private’ detective—who makes public Carol’s affair—provide only limited protection for the two women in a patriarchal culture that ultimately reinforces men’s ability to determine demarcations of public and private space. Ex Machina and Room also undermine the notion (as explored by Davidoff and Hall, 1987) that women in domestic environments are invisible from the male gaze that objectifies female bodies in the public sphere. For example, Ava and Kyoko are both subject to Nathan’s, and, to a lesser extent, Caleb’s, continuous surveillance. Nathan looks not only at, but also through, Ava, and manipulates Kyoko with a threatening orientalist gaze. He watches the women either in person or through the mediated eye of the camera and records the images on his computer. When Caleb accesses the files, he shares his findings with Ava, who, on seeing the violence done to earlier iterations of ‘artificial intelligence’ (a gendered term in the film that renders women’s intellect false and inferior to that of human men) joins forces with Kyoko to attack Nathan. However, despite Ava’s escape from her domestic prison, we know that state and institutional networks, from CCTV to Internet browsers, will continue to record her movements. The same is true for Ma. For while she breaks free from her incarceration and Old Nick’s surveillance in Room, she is continually watched by doctors, psychiatrists, family, and television viewers in the outside world. Amid increasingly visible and vocal campaigns about violence and aggression perpetrated by men against women, such as the Everyday Sexism project and Been Raped Never Reported, Carol, Ex Machina and Room all, in different ways, represent the dangers women face within the home. In a culture of surveillance that has conquered the private sphere, there are no ‘safe spaces’ for women, with technologies including voice recorders, smartphone cameras, Internet monitoring, and location geo-tagging all available to people in domestic settings. Now, ‘revenge porn’ and online trolling enter into intimate spaces (bedrooms, or personal social media accounts) that become visible sites/sights of mass consumption (websites and social media platforms). Thus the private and the public realms are conflated and the idea that the home provides safety for women, or other victims of abuse, is revealed as a myth. But while Carol, Ex Machina and Room expose the illusion, the three films also serve to perpetuate the status quo. There are other shared tropes in the films that warrant further investigation. For instance, in both Ex Machina and Room, insecurities about energy supplies are enmeshed in narratives about patriarchal power. Ma must behave according to Old Nick’s rules or he cuts Room’s gas and electricity, which enables him to assert his authority as a kind of god controlling light, dark, and heat. In Ex Machina, however, it is Ava that hacks the computer system to cause blackouts that lockdown the interior space. Here, the energy crisis is connected to anxieties about women’s interventions in public life, and the autonomous, female body’s disruptive status within patriarchal culture. More generally, the three movies allude to pervasive fears about destruction that comes from within. On the one hand, concerns about insiders breaking down social orders, flouting rules or enacting violence perhaps evoke contemporary suspicions about immigration and cultural identity. On the other, the theme might allude to the polarisation of political parties, and popularisation of right-wing rhetoric that threatens to destabilise national unity. Whatever the case, all three films are unified in the message they send to women. In a world of surveillance technology, watch out – because there’s no safe space like home, and no matter where you are, the world is always looking in on you.

6 Comments

|

BlogArchives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed