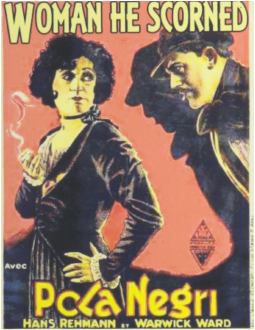

Yesterday I attended my first British Silent Film Festival Symposium, where I presented ‘Objective Cameras and Subjective Screens: The Language of First World War Cinema in Britain’. I have intended to go to the event for the past few years but for various reasons never quite made it. This year, I decided to change that and figured the best way to ensure my attendance was to send in an abstract and hope to be on the programme. As someone who works on silent cinema as part of a broader period (currently 1895 to 1948) I’ve always been slightly reluctant to submit a paper to the Symposium. My concern is that I’m not a silent cinema specialist. I certainly consider myself a silent cinema enthusiast, but my scholarship is almost accidental. I was worried that my research might not meet the standards of others who are more immersed in the field and that consequently I might face a hostile crowd. How wrong was I? BSFFS was enormously welcoming and, despite the terrifyingly large audience, proved a supportive forum for discussing any and all historical work pertaining to silent and early sound film. The varied programme showcased diverse approaches to historical work on cinema and was a fantastic reminder—if you needed one—that there are multiple, intersecting and complex histories that we are yet to discover about ‘film history’. Standout moments for me included Andrew Shail’s extraordinarily detailed detective work on the emerging star system in Europe; Emma Heslewood’s presentation on Will Onda, which included a wonderful film showing mass calisthenics; and Laraine Porter’s work on the transition from silent to sound film in the 1920s. And, of course, the screening (with live translation of intertitles, no less) of the 1929 part-talkie The Woman He Scorned. Every conversation I had during the conference taught me something I didn’t already know (special thanks to Malcolm Cook for putting me onto animated First World War maps, which I can’t wait to see), and I’ll be making sure to attend again next year. Aside from thanking the organisers (Lawrence Napper at King’s College London and the British Silent Film Festival – thanks), I want to round off this post by highlighting some great resources for anyone interested in silent film. First, Brenton Film provides an online space where you can contribute to a festival and events calendar, read blogs about silent cinema and engage with the silent film community. Second, the BECTU History Project gives researchers access to recordings of, and transcripts of interviews with, early filmmakers, stars and scholars. And third, the BFI’s BFI Player provides hours of silent and early sound film footage that is being updated regularly to include collections such as ‘Edwardian Britain on Film’ and ‘1915 on Film’. If you didn’t attend BSFFS, at least now you have a wealth of resources to get you started on your presentation for next year’s event!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

BlogArchives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed